“When you have caught the rhythm of Africa, you find out that it is the same in all her music.” — Karen Blixen

“Come over here, Michael,” says my friend and PH Geoffrey Wayland, pointing at a deserted corner on the porch of his house. “We have to talk a moment, alone.”

It is still dark and cool, a couple of hours before the African sun will paint the veldt in colors that, somehow, defy easy description. My stomach already churns from the pot of strong sweetened coffee I’ve poured down my throat.

I nod. “What’s up?”

“We have to talk about the buffalo,” Geoffrey says.

I nod again.

“Look,” says Geoffrey. “He’s going to come out today. We pushed him all day yesterday, he’s separated him from his pals. He’s old and he’s tired and he’s not going to take this crap much longer. He’s going to fight.”

Yesterday had been long slogging miles in the thorn, punctuated by moments of sheer terror, always a few steps behind the ghost in the thorn.

“You sure?”

“Sure enough that I’ve asked Leon to cancel his booking for the day and back me up with the double.”

Leon du Plessis, another good friend, is one of Ft. Richmond Safari’s PHs. Geoffrey will once again be carrying a Dakota .375 H&H. I will have my Marlin 45-70, a lever gun built by the Marlin Custom Shop to my specifications, specifically for this trip, for this day, for the shots that will come today.

“Tell me you’re 100%,” Geoffrey says

Always, I say, ignoring the fact that I got about two hours of sleep and spent most of the night going over the rifle, almost like a nervous tic, retorquing the screws that hold the Aimpoint red dot in its custom mount, a bit more oil on the lever mechanism, making sure for the umpteenth time I hadn’t overlooked anything obvious.

“How’s your knee?”

My right knee, or rather my former right knee — all the busted bones, replacement plastic parts and Rube Goldberg surgeries stitching it back together — feels like it has been hit with baseball bats swung by malevolent dwarves.

“Pretty good this morning,” I say, and Geoffrey stares at me. Geoffrey, who is always smiling and laughing, isn’t smiling or laughing. “Then let’s go do this thing,” he says.

***

I’m not sure I ever consciously planned to go to Africa, even though it loomed large in the writings of Hemingway, Ruark, Haggard, Roosevelt through most of my youth. For pretty much every other nerdy boy growing up in the South in the 1950s and ’60s. Africa was pretty much on par with Ian Fleming’s world of James Bond, Fantasyland.

Part of that was no one I knew in Tennessee had ever been to Africa. A big hunting trip for my family would be the long haul from Memphis across the bridge to Arkansas, and the biggest game was still the small whitetails that populated the verges of the soybean and cotton fields regardless of the state. Secondly, and maybe far more important, was that I had missed the hunting gene that turned opening day of deer season into a state holiday. I hunted, but for me it was always the guns. The daily eating habits of deer paled in the face of Col. Jeff Cooper, Skeeter Skelton, Charles Askins and the great gunwriters of the period.

But as no less than Robert Ruark noted, the horn of the hunter sounds early for some, later for others. A few years back I got a call from my friend Ken Jorgensen, then an exec at Ruger. He said he knew I’d turned down Africa trips before, but what would it take to get me to Africa?

“1954,” I responded.

“!954?” Ken asked. “What does that exactly mean?”

So I went on. “You know,” like 1954 safaris, 1954 National Geographic, big animals, Robert Ruark, exotic tribes, charging elephants, brutal terrain, small planes shuttling all over, gin and tonic for sundowners, campfires, amazing people…you know, 1954.”

“You don’t ask for much, do you?” he said. About a year later I got another call from Ken. “I have it,” he says.

“Have what?”

“1954.”

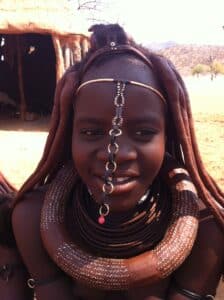

And he did — two weeks in Namibia, hunting in the Kalahari Desert with Bushmen, visiting the Himba People up on the border of Namibia and Angola, flying Cessnas along the Skeleton Coast so we could stop in Swakopmund, a town that, oddly enough, Angelina Jolie said was the most perfect place on earth, for a lazy afternoon at a German beer garden. Oh, and spending a morning with a lion pride in Etosha National Park, getting charged by a mama elephant when I stupidly stumbled into her baby while hunting mountain zebra — note, elephants are much much bigger in the wild than they seem on television — so much more that it’s probably another article, or a book.

I can, however, tell you the exact moment I was totally smitten with Africa. We’d flown into Windhoek, the only real city in Namibia, then got onboard the Cessnas to head up north to the Bushmen, more properly the San, conservatories. I was in second seat, and after a few hours we circled a red sand landing strip on the edge of the great desert. The strip was also home for a herd of giraffes. Wild giraffes, not zoo giraffes, all staring at the plane. “Somebody get out there and run those damned giraffes off the strip,” the pilot radioed. Looking at the giraffes in their ungainly gallop and a flood of wildebeests flowing in the distance, it suddenly struck me that Africa was real, and I was in love.

My second trip to Africa, South Africa this time, was with my running buddy Richard Mann, Firearms Editor at Field And Stream and as fine an outdoor writer working today, to Ft. Richmond Safaris. We got the idea to pull off the Second Scout Rifle Safari…of course, Col. Jeff Cooper did the first one, and follow in the footsteps of Frederick Russell Burnham, the great Africa scout for the British in the Boer Wars and one of Cooper’s inspirations for the Scout Rifle concept.

After that trip, Richard and I started thinking about what we wanted to do next.

“I have an idea, dude,” I said. “Cape Buffalos with 45-70 lever guns.”

“That,” said Richard, “rocks!”

So with the help of our longtime friend Carlos Martinez, then head of the Marlin Custom Shop, and Remington’s fading bank account, we scheduled a trip back to South Africa and Ft. Richmond Safaris, specifically for buffalo.

Before we get into the weeds, or the thorns, as it were, let me tell you a bit about hunting with a film crew. It sucks. It’s like hunting while dragging a couple of tires on chains behind you. It’s the nature of the beast…you’re there for the video, which means all the dominos need to line up to make sure to get the video. My crew was aways better than most, but it still is a conga line weaving through the terrain.

There is also the added element of hunting dangerous game. It goes without saying that a Cape Buffalo can gore, stomp and otherwise disassemble you in a myriad number of ways, all of which appear to be extraordinarily painful and usually fatal. That has big implications for filming. While stalking the dread whitetail deer, I will listen to the whispers of my crew…speed up…slow down…don’t shoot…let us get in position…etc. All that goes out the window with dangerous game. The hunter, e.g. me, needs to remain totally focused on the task at hand, namely avoiding becoming another hunting statistic.

While we are still in the planning stages, I read every word I could find on “Black Death”…Ruark, Boddington, Burger, Capstick, plus the flood of contradictory stories on Ye Olde Internet. Then I called two of my best friends who have a couple of lifetime’s experience with buffalos, Tim Wegner and Larry Potterfield. Both Tim — founder of Blade-Tech Holsters, gourmet cook and old Africa hand — and Larry, whom I’m pretty sure needs no introduction, are two of the people I would trust with my life. What am I overlooking, I ask? What do I need to know?

First thing Tim and I did was huddle up with Tim Sundles from Buffalo Bore Ammo on what type of bombs we could launch out of a 45-70. We settled on 430-gr hard-cast lead flat-nose at around 1,925 feet per second. Do the math and it ends up 3537 foot-pounds of energy, which would put that load between a .405 Winchester and a 450/400 3-inch Nitro Express in overall thump.

The gun I’d spec’ed from the Marlin Custom Shop was an 1895 Cowboy 45-70 with an octagonal barrel cut to 18 inches, a straight stock and a Skinner “Express” peep sight on the receiver that would also mount an Aimpoint Hunter H30S with a 2MOA red dot. Up close I have found nothing works as well — or as fast — as an electronic dot sight. With the sight, a leather butt cuff with a half-inch of Sorbothane in it and a leather wrap for the lever, the whole gun came in at a spec over 7 pounds, three-quarters of a pound less than a Ruger #1 450/400 with no sights, more than 3 pounds lighter than a Krieghoff double in 450/400.

Of course the Custom Shop couldn’t help themselves…the little rifle came with #1 wood, hand-cut checkering, flawless wood-to-metal fit and a color-case hardening job from Doug Turnbull. “You know I’m going to ruin this beautiful finish,” I said. “Don’t worry,” Carlos said. “We built it; we can rebuild it.”

The Marlin handled as well an any rifle I had ever put to my shoulder…no, that doesn’t nearly explain it. The gun was pure-D magic, as we would say in the South, the kind of gun you dreamed about from the first time you picked up a rifle. It shouldered and balanced like a fine shotgun, pointed superbly. And with Buffalo Bore dinosaur killers, the recoil was right on up there in Detached Retina Land.

“What did you expect?” Tim asked. Besides, he added, I wouldn’t feel a thing until the next day, unless of course I was dead, in which case I wouldn’t feel a thing anyway.

“Okay, here’s the training regimens according to Tim,” Tim said. “No more than 3 dinosaur killers a week, if that. You still got that .44 Magnum Marlin Wild West Guns built for you?”

Sure, I said.

“Well, that’s your training rifle, and you’re going to shoot it a lot!”

Let me say that I spent 10 years as a pretty good Cowboy Action Shooter, and I grew up in Tennessee with Winchester 94s. I’ve taken classes with lever guns, hunted pigs with them, I know on some DNA level how to run a lever gun. So I bought a couple of cases of 240-gr JHP .44 Magnums and I started shooting.

I worked a lot off sticks, de rigueur in Africa, and what I think of as “broken” positions…off piles of rocks, tree limps, prone with the gun raised on a log, etc. What proved to be the most important things were drills from Mr. Potterfield, especially the “charging” drill.

“How fast can a Cape Buffalo cover 50 yards?” Larry asked me.

I wasn’t sure.

“Seven seconds,” he said. “All you have is 7 seconds if he’s 50 yards away.” So the basic drill was a target at 50 yards, a target at 25 yards and a small target at seven yards, with a par-time of 7 seconds set on a shot-timer. I had a 12-inch plate at 50 yards, a 10-inch plate at 25 yards and an 8-inch plate at 7 yards. I shot that drill a lot, pretty much until I saw it in my sleep.

I worked on “swing drills,” first shot off the sticks, swing 20 degrees for the second off-hand shot, which will be farther away, 30 degrees for the longest shot, simulating a wounded animal running away. I was also lucky enough to get some time on the “safari simulator” at FTW Ranch in Texas, one of my favorite places in the entire world, shooting charging buffalo targets or buffalos that sprang from the underbrush on their mechanized safari trail. If you’re going to Africa, you owe it to yourself…and your PH…to spend a few days at FTW…they have been there, done that and will make your African experience so much better. Maybe even keep you alive.

Before the trip, I’m filming a segment of SHOOTING GALLERY with a friend of mine, a famous hunter, as a guest. During a break, he says, “You’re hunting buffalo with a 45-70, I hear.” It is a small, small, small, small world indeed.

“You’re undergunned,” he says.

I know, I reply, making light. “I read Ruark.” USE ENOUGH GUN is Ruark’s classic book.

“No, seriously, Michael, you’re way undergunned,” the hunter, who has legitimately forgotten more about Cape Buffalo in the previous 30 minutes than I will ever know, says. I’m good, I say. He shakes his head.

No worries, I say and think that if indeed Black Death succeeds in skewering me, followed by trampling me into a muddy, bloody mess, I have no doubt my friend will be able to write an excellent obit, starting with, “I told him so.”

And then, with all the paperwork in place — it really helps to have done this before — we head to Africa.

***

Geoffrey and I, in the thorn….

Let me tell you a little about Ft. Richmond Safaris and the Wayland family. When you go, it’s like being adopted into a large, very friendly family. That family has owned and managed the Ft. Richmond property, about an hour and a half from Kimberly, the diamond capitol of the world, and near the Orange River, since 1869. You have your meals in the family home, usually the previous day’s successful hunt, under the supervision of Victoria Wayland, Geoffrey’s wife…did I mention she was a chef on cruise ships? Specializing in desserts? Be still my beating heart.

The current Wayland, Geoffrey, learned his bush skills at the feet of his late father, famous professional hunter Neil Wayland. Geoffrey’s grandfather, John, was an early adopter of a holistic approach to managing the land, even reintroducing indigenous species long gone.

It’s the veld, defined as a flat area covered in grass and scrub brush, but the definition doesn’t do it justice. Its actually it’s lots of velds…thornvelds, sand velds, pan velds…along with pans, areas of karoo (think desert) and kopjes, small hills. In fact, the ecosystem is amazingly varied, and if you want the details, Geoffrey can tell you down to the minutest.

The first thing Geoffrey and I do is hammer out the details. You may not know this, but one of the most important things for you to do with a guide or professional hunter is to let them know what your expectations are. And they, in turn, will tell you how close they can come to meeting those expectations. Because I’d hunted with Geoffrey before and he understood the necessities of filming for television, it was easy-peasy.

“No farther than 50 yards. Preferably in undergrowth.”

Sure, Geoffrey says. “Just remember, this is your hunt. I won’t take a shot for you. I’ll try to save you if you screw up.”

More than this, I say, I’d never ask.

I’m not first up in the hunting rotation, so Carlos Martinez goes out before me. His long barreled 45-70 takes an excellent bull at 100 or so yards. I spend a day with Richard Mann hunting zebra with his 45-70 Marlin. That afternoon Geoffrey tells me that he’s found a situation that just might work for filming. Seems there’s a “problem” buffalo on one of the large ranches bordering a national park, likely in a “paddock.”

“Paddock,” I ask? “Like a pen?”

“Yeah right,” Geoffrey says. ” A 5,000, maybe 10,000 acre pen.”

In Africa, words have different meanings. Terrain?

“Sixty, 70 percent thorn,” Geoffrey says. “With kopjes scattered around. He’s going to be hard to find in the thorn. Understand this, Michael — he’s old and he’s smart and he’s dangerous, and he’s going to be pissed off. You gotta know this going in.”

Thank you, I say. I’m good. Apparently, this is my universal answer for pretty much everything.

“Brief your crew,” Geoffrey says. “Make sure they understand things can get sketchy quick.”

Before dawn the next morning, we’re on our way.

Geoffrey wasn’t joking about the thorn. It was like staring into hedgerows from hell. I already knew from earlier visits that every plant in Africa wants to hurt you…they hook, they stab, they slice, you bleed. The thing is that thorns doesn’t look particularly dense until you’re in it, and you realize they’re impervious to sight. You can’t see a damn thing through them.

The thorn is cut through with hundreds of animal trails, meandering all over the place. Most of them are dead-ends, as if the animal abruptly got tired of being poked by thorn and finally teleported out. Our plan should be familiar to anyone who seen any African hunting shows…we’ll drive around in the safari car until we see tracks, of if we’re really lucky the tail end of a buffalo’s tail as he slips away. Then it’s time for Geoffery, me and the trackers to dismount and walk.

For a couple of hours its no joy. We do a lot of tracks that amount of nothing. And then we get a bit of luck and actually see that disappearing buffalo tail at the end of a long corridor in the thorn. We pick up the pace…for hours. No buffalo. Its like tracking smoke though a maze. What’s worse is now we’re deep into the thorn, and visibility has pretty much dropped to less than zero.

“He’s got to be in here somewhere,” Geoffrey whispers. “I swear I can feel him. Head on a swivel. He’s got to be…”

There is a loud snort from the other side of a thorn wall, three, maybe four, feet away from us. Spitting distance, as they say.

I hear Geoffrey whisper something that sound suspiciously like a very bad word you don’t want to hear from your PH.

And the huge black boss suddenly appears above the thorn. The bull’s rheumy, bloodshot eyes lock on mine as both Geoffrey and I frantically struggle to get the guns in play. At three feet, we are inside the hook of his horns; all the bull has to do is shake his great head and we are in serious, deadly, trouble. The bull looks at me…forever…maybe two forevers…so you’re the monkey who’s pestering me, the eyes seem to say…you and I will have business, but not today. Then he snorts again, turns and trots away.

“Holy shit!” the videographer says loudly.

“Safe your gun,” Geoffrey says to me. Adrenaline is boiling through my system like some teakettle gone berserk; I expect there is stream coming out of my ears. I put the safety on the Marlin, lower the hammer, then click the safety off. I notice Geoffrey is breathing a little heavy himself. Then he grins.

“Well,” he says. “That was different.”

“So,” says the videographer as I struggle to get my heart rate out of the stratosphere, “we weren’t really in danger, were we? You and Michael could still have shot him, right.”

“We could have shot him,” Geoffrey says, “but we couldn’t have stopped him.”

“Should I have run?” the videographer asks.

“If you had run,” Geoffrey says, “he would have killed you.”

***

Before we go on, I think I should talk a little about facing death…but first, how pizza figures into that.

We have to go back a ways when I lived in Tampa, not far from the beach, writing about the then-new world of personal computers. I had a plumb gig as one of the premier tech writers for the Chicago Tribune News Syndicate, and I got to hang out at places like the MIT Media Lab with the people who were inventing the future. In my spare time, I went windsurfing, because, hey, the beach.

One day I was sitting in my office writing something about how the world was changing when I heard the wind come up. It started low, and over a couple of hours built into a howl. I saw palm fronds, garbage can lids and all manner of detritus come sailing past my office window, and this little voice in my head said, “Hey! Let’s go windsurfing.”

The wind was gusting over 50 by the time I got to the beach, and I launched myself into a maelstrom of wind and water. I wasn’t so much sailing as hanging on for dear life. When the wind finally died off, I was still pumped, my hands bloody from fighting the sail. So I did the only thing I could think of to do…I called a bunch of my friends and said I’d meet them at our favorite pizza and beer place to regale them with stories of my day sailing.

In the course of that evening, when the bartender had finally cut us off and called taxis to take us home, a friend of mine said, “Hey, why don’t we make a list of crazy athletic events? You know, shit than can kill you?”

So with the waitress’ pen and a cocktail napkin, we created the Shit That Can Kill You List, 13 things ranging from moderate, say rock climbing, to relatively nuts, say scuba diving in caves. As the taxis arrived, my friend held up the cocktail napkin. “What are you going to do with the List, Michael?” he said.

I fuzzily thought for a minute, then said, “I think I’ll do everything on the List then write a book about it.”

“Sure,” he said.

The punchline is that four years, all the money I had in the world and one long-term relationship later (“You’ve lost your mind over that stupid List!“), I finished. The book is called OVER THE EDGE: A REGULAR GUY’S ODYSSEY IN EXTREME SPORTS, by the way, and it led the Wall Street Journal to call me, “the George Plimpton from Hell.”

Here’s a spoiler alert: I didn’t die. but to say OVER THE EDGE changed my life is a vast, vast understatement. But without making a long story longer, let me cut to Item #13 on the List, “Climb Denali in Alaska.”

Denali, Mt. McKinley if you will, is at 20,310 feet the highest mountain in North America and is considered by the native tribes of Alaska as a god, or at least a place where the gods lived. They weren’t wrong. Denali is technically a “walk up,” meaning that there is no technical climbing required, although climbers will be roped into teams of five for most of the long, cold slog. The catch is that if you don’t take Denali seriously, it can and will kill you, as it does a few climbers every year. The weather is crazy, with occasionally brutal storms and stunning low temperatures. Freezing your ass off is a real thing.

After a year of basically insane training, I head to Denali in May, part of an experienced team going in early to ideally swap the storms of summer with the bitter cold of spring. As it happens, we got both. After about two weeks on the mountain…climbing high, slogging back down to the previous camp to sleep low, then haul gear up in the morning, we were trapped at about 15,000 feet by a screaming blizzard that dumped five feet of snow on our fortified campsite. Our tents were surrounded by quarried snow-block walls, and every few hours my tentmate and I flipped a coin to see who would go outside in the 20-below temperatures to clear enough snow off the tent vent so we wouldn’t suffocate in our sleep.

As the storm tailed off we emerged from our now-covered snow forts like gophers in the spring. One intrepid team of climbers immediately headed up, betting that the storm had spent its fury. But the storm still had teeth, and two climbers paid for that bet with their lives. I remember mostly how excited they were to get back on the trail. Rescue managed to get a high-altitude helicopter made mostly out of carbon fiber and faith up to remove the bodies. Each body was suspended from the little helicopter’s skids on climbing ropes, and as the copter rose, the bodies spun like compass needles.

“Gentleman,” our guide said as we watched the second body spin on the rope, “no mistakes. No mistakes at all.”

Once we were under way again underneath perfect blue skies and bone-chilling cold, we made good time. A lot of teams were bunched together was we moved over a crevasse field, everyone picking their way across carefully across the crevasses, lest we end up in as part of a glacier in Anchorage in a millennium or so. There was a sound like thunder, an anomaly in the perfect weather, and as I looked toward the high ridge line to my left, I saw the snow-loaded ridge let go. The crack started at one end of the ridge and raced across the whole face launching a mountain of snow…toward us.

The thunder was constant, and someone shouted, “Run!” I heard our guide say, “Where?” but he said it softly. People were screaming and scattering where they could; some were on their knees praying and the great wall of the avalanche, roaring like a cosmic train, kept coming. The man on the rope behind me laughed. He was, if I remember, a banker who’d worked in the Middle East, a veteran climber. I pulled my eyes away from the avalanche, looked at him and asked, “What’s funny?”

“It’s all so simple now,” he said. “It’s a simple binary choice.” He pointed toward the white wall closing in. “Do we face it, or do we turn away.”

“I have never been one for turning away,” I said.

He smiled. “Insha’Allah.”

As God wills it.

“Insha’Allah,” I said, and turned to face the mountain.

But those Gods of Denali were kind, and as if by that cosmic Hand the mountain of snow was swept into the crevasse field, vanishing like a cartoon avalanche. A wall of wind and frozen grit hit hard enough to knock people down, but we were all alive. The man behind me on the rope smiled, and so did I.

***

We hike back to the safari truck for a quick, late lunch, and then pick up the trail again. Or attempt to pick up the trail. Wherever the buffalo was, he’s no longer there. In fact, he no longer seems to be anywhere. Instead, we tramp the thorn, across open areas that seem like someone has dumped truckload of bowling balls disguised as rocks. Somewhere along the way, my right leg snags and torques, and the white hot pain surges through my sort-of knee. Geoffrey looks back at me, and I shrug.

Tracks go nowhere. It’s like the buffalo is leading us on a merry-go-round through the thorn. In the safari truck we crisscross trails I swear I’ve seen two or there times before.

“Where is he?” Geoffrey mutters to himself.

With shooting light fading, we get a break as one of the trackers spots movement maybe a quarter-mile away. We start moving quickly. The buffalo seems to be moving out of the thorn and onto open ground. We once again catch a glimpse of something, and with the adrenaline up, we push hard around a little kopje, certain that my shot will come as we hook around the buffalo’s trail.

We perfectly hook around the buffalo’s trail, but the buffalo isn’t there. We’re out of the thorn. There’s nowhere for him to hide. But he is Simply. Not. There.

And then we look up the kopje. Near the top in the fading light, the buffalo stands watching us. He has us checkmated and he knows it. If we go up, he goes down into the thorn as the sun sets. If we try and wait him out, the dark will catch us in just a few minutes. Playing tag with a Cape Buffalo in the dark doesn’t seem like a wise idea to any of us. Short of calling in an air strike, he’s out of our reach.

We head back to the truck, a dispirited group. It’s slow going, as I am limping now.

“We’ll get him tomorrow,” Geoffrey says.

I agree, visions of Advil dancing in my head.

After our ex-officio meeting in the morning before we leave, the next day’s hunt begins much as the first one ended…in the thorn. The weather’s mild, but the day is heating up, and the thorn adds a claustrophobic intensity to the stalks. The first hours drag, I think mostly because we’re all remembering the buffalo, standing on the kopje looking down on us annoying monkeys.

“When he decides to fight, he’ll come at you from the shadows,” Geoffrey says. “He’ll back into the thorn and he’ll be hard to see, but he’ll see you just fine. It’ll happen quick. And even if you get a heart shot, he can continue going for five minutes. This is the toughest animal on earth.”

I nod. We decide to drive some more and look for tracks. After a couple of fruitless stalks, we are not far from where we started, our first encounter. The tracks, however, are fresh. We’re out of the truck in a flash. Geoffrey nods at Leon and the tracker, and we’re off on the stalk, heads on a swivel.

We come out of the thorn into a small clearing. Geoffrey rounds a small bush and stops.

“He’s here,” Geoffrey whispers urgently for me to come alongside him. “In the shadow.”

The Marlin shouldered, I look through the Aimpoint into the shadow and see nothing. But then the slightest movement, and the shadow dissolves into the front of the buffalo, less than 40 yards away, his eyes now locked on mine. His right hoof slightly paws the ground, and his eyes say it is time to conclude the business between us. Out of the corner of my eye I see Geoffrey with the .375 at the ready; on the other side I see Leon shouldering the double.

Forty yards, I think absently…six seconds, Mr. Potterfield.

Then the universe slows to a crawl. Not only do I feel my heartbeat drop, but a wave of calm washes over me. It’s all so simple now, a simple binary choice. Geoffrey whispers the aiming point, and the red dot is there. I neither hear the blast of the 45-70 nor feel the recoil slamming into my shoulder. But I do hear the thwack of the heavy bullet slamming deep into the buffalo’s chest and heart. Through the sight see him go to his knees. The Marlin’s already levered for the next shot. There is a moment of a frozen tableau, all of us, the kneeling buffalo, me, Geoffrey, Leon, even the tracker and videographer frozen in place.

And then the buffalo comes out.

He is magnificent, fury personified, launched from his kneeling position like a rodeo bull out of the gate, his great horns lowered to make mincemeat of his attacker. I hear Geoffrey as I’m swinging the rifle on the buffalo. When all four hooves hit the ground. More than half the distance between us now gone, and as all four hooves touch the ground the buffalo turns slightly, choosing his target.

Once again, I neither hear the shot — a spine shot — or feel the recoil, but the 45-70 knocks the buffalo off his feet. I feel my head cycling back into Real Time and start to take a step forward. Geoffrey grabs me by the shoulder. “Dead buffalos kill hunters,” he says. And the great beast attempts to rise one more time. “Through the shoulders,” Geoffrey says, about the only shot I have. “Break him down.”

The third shot goes through the shoulders, and the buffalo will rise no more. Instead, he raises his head one last time and lets go a long mournful bellow, one final entreaty to the Horned God, I think, or maybe he’s just calling out his name in the face of the coming Dark. He has never known fear, and I don’t think he knows it now.

Geoffrey waves away the camera people and shepherds us away to a small copse of trees.

“Let’s give the old king the dignity he deserves,” Geoffrey says, and the cameras are lowered. That way they don’t record the tears in my eyes.

***

There is a party that night at Ft. Richmond to celebrate my and Carlos’ successful hunts, and it is magical. A spectacular table is set outside beneath trees twinkling with small lights. World class food is served to world class company, and excellent champagne is popped. The first toast is, of course, to the Cape Buffalos, may they roam forever. The cork from that champagne bottle hangs over my desk as I write. It is a night to remember, something to hang on to in the cold pandemic days that will come.

The campfire burns down to glowing embers, and the evening air carries a chill bite. The scotch is soothing warmth. Richard, who calls himself a hillbilly, and I share the last of the campfire, as we have done many times before, savoring a deep African rhythm that leads back to the Bushman who first hunted this land. I am silent, and Richard finally says, “You know, Michael, you gave that buffalo something, too.”

I look up from the scotch, questioning.

“A warrior’s death.”

I nod. You gotta hand it to those hillbillies.

— 30 —

[A version of this story appeared in the SCI magazine SAFARI MAGAZINE, Jul/Aug 2022 edition. Photos by Michael Bane and/or courtesy Outdoor Channel/SHOOTING GALLERY]

Here I am trying too get through four days worth of Holiday Sale emails, and Michael drops the longest post in ages. Good work on this.

Thanks for taking me with you, man. I’ll never get to do it myself.

Thank you for sharing this great story! You do have a gift in writing them!